Scenic Tutorial¶

This tutorial motivates and illustrates the main features of Scenic, focusing on aspects of the language that make it particularly well-suited for describing geometric scenarios. Throughout, we use examples from our case study using Scenic to generate traffic scenes in GTA V to test and train autonomous cars [F19].

Classes, Objects, and Geometry¶

To start, suppose we want scenes of one car viewed from another on the road. We can write this very concisely in Scenic:

1 2 3 | from scenic.simulators.gta.model import Car

ego = Car

Car

|

Line 1 imports the GTA world model, a Scenic library defining everything specific to our

GTA interface. This includes the definition of the class Car, as well as information

about the road geometry that we’ll see later. We’ll suppress this import statement in

subsequent examples.

Line 2 then creates a Car and assigns it to the special variable ego specifying the

ego object. This is the reference point for the scenario: our simulator interfaces

typically use it as the viewpoint for rendering images, and many of Scenic’s geometric

operators use ego by default when a position is left implicit (we’ll see an example

momentarily).

Finally, line 3 creates a second Car. Compiling this scenario with Scenic, sampling a

scene from it, and importing the scene into GTA V yields an image like this:

A scene sampled from the simple car scenario, rendered in GTA V.¶

Note that both the ego car (where the camera is located) and the second car are both

located on the road and facing along it, despite the fact that the code above does not

specify the position or any other properties of the two cars. This is because in Scenic,

any unspecified properties take on the default values inherited from the object’s

class. Slightly simplified, the definition of the class Car begins:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | class Car:

position: Point on road

heading: roadDirection at self.position

width: self.model.width

height: self.model.height

model: CarModel.defaultModel() # a distribution over several car models

|

Here road is a region, one of Scenic’s primitive types, defined in the gta model

to specify which points in the workspace are on a road. Similarly, roadDirection is a

vector field specifying the nominal traffic direction at such points. The operator

F at X simply gets the direction of the field F at point X, so line 3

sets a Car’s default heading to be the road direction at its position. The default

position, in turn, is a Point on road (we will explain this syntax shortly),

which means a uniformly random point on the road. Thus, in our simple scenario above both

cars will be placed on the road facing a reasonable direction, without our having to

specify this explicitly.

We can of course override the class-provided defaults and define the position of an object more specifically. For example,

1 | Car offset by (-10, 10) @ (20, 40)

|

creates a car that is 20–40 meters ahead of the camera (the ego), and up to 10

meters to the left or right, while still using the default heading (namely, being aligned

with the road). Here the interval notation (X, Y) creates a uniform

distribution on the interval, and X @ Y creates a vector from xy

coordinates (as in Smalltalk [GR83]).

Local Coordinate Systems¶

Scenic provides a number of constructs for working with local coordinate systems, which

are often helpful when building a scene incrementally out of component parts. Above, we

saw how offset by could be used to position an object in the coordinate system of the

ego, for instance placing a car a certain distance away from the camera 1.

It is equally easy in Scenic to use local coordinate systems around other objects or even arbitrary points. For example, suppose we want to make the scenario above more realistic by not requiring the car to be exactly aligned with the road, but to be within say 5°. We could write

1 2 | Car offset by (-10, 10) @ (20, 40),

facing (-5, 5) deg

|

but this is not quite what we want, since this sets the orientation of the car in

global coordinates. Thus the car will end up facing within 5° of North, rather than

within 5° of the road direction. Instead, we can use Scenic’s general operator

X relative to Y, which can interpret vectors and headings as being in a

variety of local coordinate systems:

If instead we want the heading to be relative to that of the ego car, so that the two

cars are (roughly) aligned, we can simply write (-5, 5) deg relative to ego.

Notice that since roadDirection is a vector field, it defines a different local

coordinate system at each point in space: at different points on the map, roads point

different directions! Thus an expression like 15 deg relative to field does not

define a unique heading. The example above works because Scenic knows that the

expression (-5, 5) deg relative to roadDirection depends on a reference position, and

automatically uses the position of the Car being defined. This is a feature of

Scenic’s system of specifiers, which we explain next.

Readable, Flexible Specifiers¶

The syntax offset by X and facing Y for specifying positions and

orientations may seem unusual compared to typical constructors in object-oriented

languages. There are two reasons why Scenic uses this kind of syntax: first, readability.

The second is more subtle and based on the fact that in natural language there are many

ways to specify positions and other properties, some of which interact with each other.

Consider the following ways one might describe the location of an object:

“is at position X” (an absolute position)

“is just left of position X” (a position based on orientation)

“is 3 m West of the taxi” (a relative position)

“is 3 m left of the taxi” (a local coordinate system)

“is one lane left of the taxi” (another local coordinate system)

“appears to be 10 m behind the taxi” (relative to the line of sight)

“is 10 m along the road from the taxi” (following a potentially-curving vector field)

These are all fundamentally different from each other: for example, (4) and (5) differ if the taxi is not parallel to the lane.

Furthermore, these specifications combine other properties of the object in different

ways: to place the object “just left of” a position, we must first know the object’s

heading; whereas if we wanted to face the object “towards” a location, we must

instead know its position. There can be chains of such dependencies: for example,

the description “the car is 0.5 m left of the curb” means that the right edge of the

car is 0.5 m away from the curb, not its center, which is what the car’s position

property stores. So the car’s position depends on its width, which in turn

depends on its model. In a typical object-oriented language, these dependencies might

be handled by first computing values for position and all other properties, then

passing them to a constructor. For “a car is 0.5 m left of the curb” we might write

something like:

# hypothetical Python-like language

model = Car.defaultModelDistribution.sample()

pos = curb.offsetLeft(0.5 + model.width / 2)

car = Car(pos, model=model)

Notice how model must be used twice, because model determines both the model of

the car and (indirectly) its position. This is inelegant, and breaks encapsulation

because the default model distribution is used outside of the Car constructor. The

latter problem could be fixed by having a specialized constructor or factory function:

# hypothetical Python-like language

car = CarLeftOfBy(curb, 0.5)

However, such functions would proliferate since we would need to handle all possible combinations of ways to specify different properties (e.g. do we want to require a specific model? Are we overriding the width provided by the model for this specific car?). Instead of having a multitude of such monolithic constructors, Scenic factors the definition of objects into potentially-interacting but syntactically-indepdendent parts:

1 2 | Car left of spot by 0.5,

with model CarModel.models['BUS']

|

Here left of X by D and with model M are specifiers which do not

have an order, but which together specify the properties of the car. Scenic works out

the dependencies between properties (here, position is provided by left of, which

depends on width, whose default value depends on model) and evaluates them in the

correct order. To use the default model distribution we would simply omit line 2; keeping

it affects the position of the car appropriately without having to specify BUS

more than once.

Specifying Multiple Properties Together¶

Recall that we defined the default position for a Car to be a Point on road:

this is an example of another specifier, on region, which specifies

position to be a uniformly random point in the given region. This specifier

illustrates another feature of Scenic, namely that specifiers can specify multiple

properties simultaneously. Consider the following scenario, which creates a parked car

given a region curb (also defined in the scenic.simulators.gta.model library):

1 2 | spot = OrientedPoint on visible curb

Car left of spot by 0.25

|

The function visible region returns the part of the region that is visible from

the ego object. The specifier on visible curb with then set position to be a

uniformly random visible point on the curb. We create spot as an OrientedPoint,

which is a built-in class that defines a local coordinate system by having both a

position and a heading. The on region specifier can also specify

heading if the region has a preferred orientation (a vector field) associated with

it: in our example, curb is oriented by roadDirection. So spot is, in fact,

a uniformly random visible point on the curb, oriented along the road. That orientation

then causes the Car to be placed 0.25 m left of spot in spot’s local coordinate

system, i.e. 0.25 m away from the curb, as desired.

In fact, Scenic makes it easy to elaborate this scenario without needing to alter the

code above. Most simply, we could specify a particular model or non-default distribution

over models by just adding with model M to the definition of the Car. More

interestingly, we could produce a scenario for badly-parked cars by adding two lines:

1 2 3 4 | spot = OrientedPoint on visible curb

badAngle = Uniform(1, -1) * (10, 20) deg

Car left of spot by 0.25,

facing badAngle relative to roadDirection

|

This will yield cars parked 10-20° off from the direction of the curb, as seen in the image below. This example illustrates how specifiers greatly enhance Scenic’s flexibility and modularity.

A scene sampled from the badly-parked car scenario, rendered in GTA V.¶

Declarative Hard and Soft Constraints¶

Notice that in the scenarios above we never explicitly ensured that two cars will not intersect each other. Despite this, Scenic will never generate such scenes. This is because Scenic enforces several default requirements:

All objects must be contained in the workspace, or a particular specified region. For example, we can define the

Carclass so that all of its instances must be contained in the regionroadby default.Objects must not intersect each other (unless explicitly allowed).

Objects must be visible from the ego object (so that they affect the rendered image; this requirement can also be disabled, for example for dynamic scenarios).

Scenic also allows the user to define custom requirements checking arbitrary conditions built from various geometric predicates. For example, the following scenario produces a car headed roughly towards the camera, while still facing the nominal road direction:

1 2 3 | ego = Car on road

car2 = Car offset by (-10, 10) @ (20, 40), with viewAngle 30 deg

require car2 can see ego

|

Here we have used the X can see Y predicate, which in this case is checking

that the ego car is inside the 30° view cone of the second car.

Requirements, called observations in other probabilistic programming languages, are

very convenient for defining scenarios because they make it easy to restrict attention to

particular cases of interest. Note how difficult it would be to write the scenario above

without the require statement: when defining the ego car, we would have to somehow

specify those positions where it is possible to put a roughly-oncoming car 20–40 meters

ahead (for example, this is not possible on a one-way road). Instead, we can simply place

ego uniformly over all roads and let Scenic work out how to condition the

distribution so that the requirement is satisfied 2. As this example illustrates,

the ability to declaratively impose constraints gives Scenic greater versatility than

purely-generative formalisms. Requirements also improve encapsulation by allowing us to

restrict an existing scenario without altering it. For example:

1 2 3 | import genericTaxiScenario # import another Scenic scenario

fifthAvenue = ... # extract a Region from a map here

require genericTaxiScenario.taxi on fifthAvenue

|

The constraints in our examples above are hard requirements which must always be satisfied. Scenic also allows imposing soft requirements that need only be true with some minimum probability:

1 | require[0.5] car2 can see ego # condition only needs to hold with prob. >= 0.5

|

Such requirements can be useful, for example, in ensuring adequate representation of a particular condition when generating a training set: for instance, we could require that at least 90% of generated images have a car driving on the right side of the road.

Mutations¶

A common testing paradigm is to randomly generate variations of existing tests. Scenic supports this paradigm by providing syntax for performing mutations in a compositional manner, adding variety to a scenario without changing its code. For example, given a complex scenario involving a taxi, we can add one additional line:

1 2 | from bigScenario import taxi

mutate taxi

|

The mutate statement will add Gaussian noise to the position and heading

properties of taxi, while still enforcing all built-in and custom requirements. The

standard deviation of the noise can be scaled by writing, for example,

mutate taxi by 2 (which adds twice as much noise), and in fact can be controlled

separately for position and heading (see scenic.core.object_types.Mutator).

A Worked Example¶

We conclude with a larger example of a Scenic program which also illustrates the language’s utility across domains and simulators. Specifically, we consider the problem of testing a motion planning algorithm for a Mars rover able to climb over rocks. Such robots can have very complex dynamics, with the feasibility of a motion plan depending on exact details of the robot’s hardware and the geometry of the terrain. We can use Scenic to write a scenario generating challenging cases for a planner to solve in simulation.

We will write a scenario representing a rubble field of rocks and piples with a

bottleneck between the rover and its goal that forces the path planner to consider

climbing over a rock. First, we import a small Scenic library for the Webots robotics

simulator (scenic.simulators.webots.mars.model) which defines the (empty) workspace

and several types of objects: the Rover itself, the Goal (represented by a flag), and

debris classes Rock, BigRock, and Pipe. Rock and BigRock have fixed sizes, and

the rover can climb over them; Pipe cannot be climbed over, and can represent a pipe of

arbitrary length, controlled by the height property (which corresponds to Scenic’s

y axis).

1 | from scenic.simulators.webots.mars.model import *

|

Then we create the rover at a fixed position and the goal at a random position on the other side of the workspace:

2 3 | ego = Rover at 0 @ -2

goal = Goal at (-2, 2) @ (2, 2.5)

|

Next we pick a position for the bottleneck, requiring it to lie roughly on the way from the robot to its goal, and place a rock there.

4 5 6 7 | bottleneck = OrientedPoint offset by (-1.5, 1.5) @ (0.5, 1.5),

facing (-30, 30) deg

require abs((angle to goal) - (angle to bottleneck)) <= 10 deg

BigRock at bottleneck

|

Note how we define bottleneck as an OrientedPoint, with a range of possible

orientations: this is to set up a local coordinate system for positioning the pipes

making up the bottleneck. Specifically, we position two pipes of varying lengths on

either side of the bottleneck, with their ends far enough apart for the robot to be able

to pass between:

8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | halfGapWidth = (1.2 * ego.width) / 2

leftEnd = OrientedPoint left of bottleneck by halfGapWidth,

facing (60, 120) deg relative to bottleneck

rightEnd = OrientedPoint right of bottleneck by halfGapWidth,

facing (-120, -60) deg relative to bottleneck

Pipe ahead of leftEnd, with height (1, 2)

Pipe ahead of rightEnd, with height (1, 2)

|

Finally, to make the scenario slightly more interesting, we add several additional obstacles, positioned either on the far side of the bottleneck or anywhere at random (recalling that Scenic automatically ensures that no objects will overlap).

15 16 17 18 19 20 | BigRock beyond bottleneck by (-0.5, 0.5) @ (0.5, 1)

BigRock beyond bottleneck by (-0.5, 0.5) @ (0.5, 1)

Pipe

Rock

Rock

Rock

|

This completes the scenario, which can also be found in the Scenic repository under

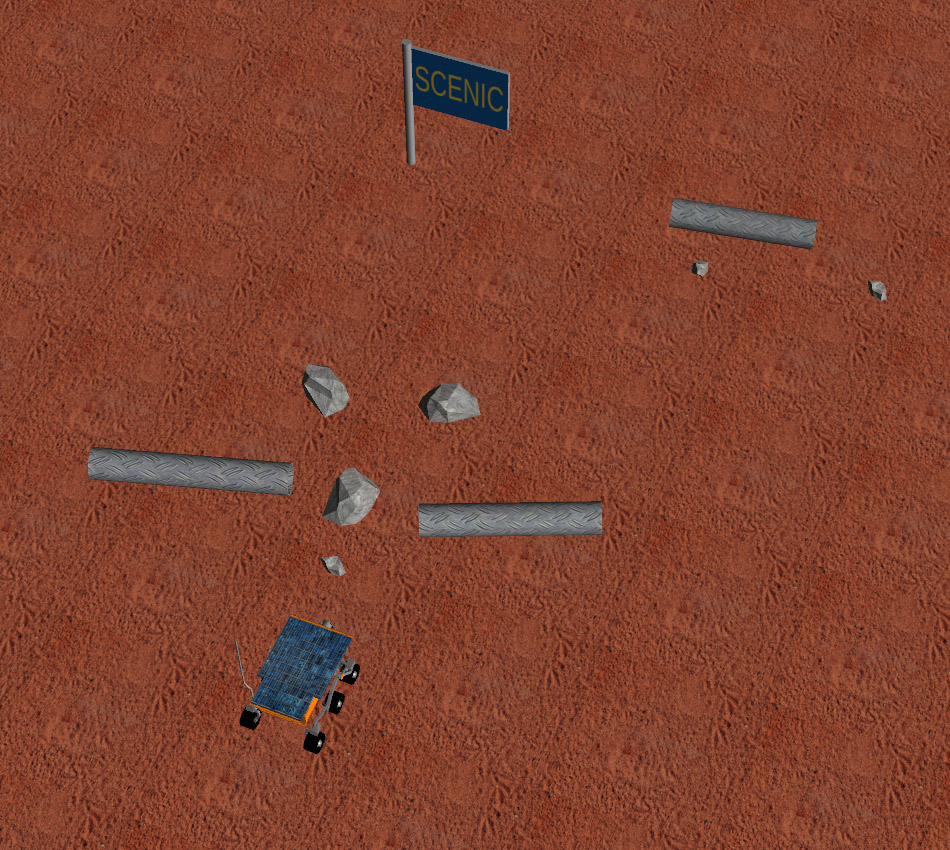

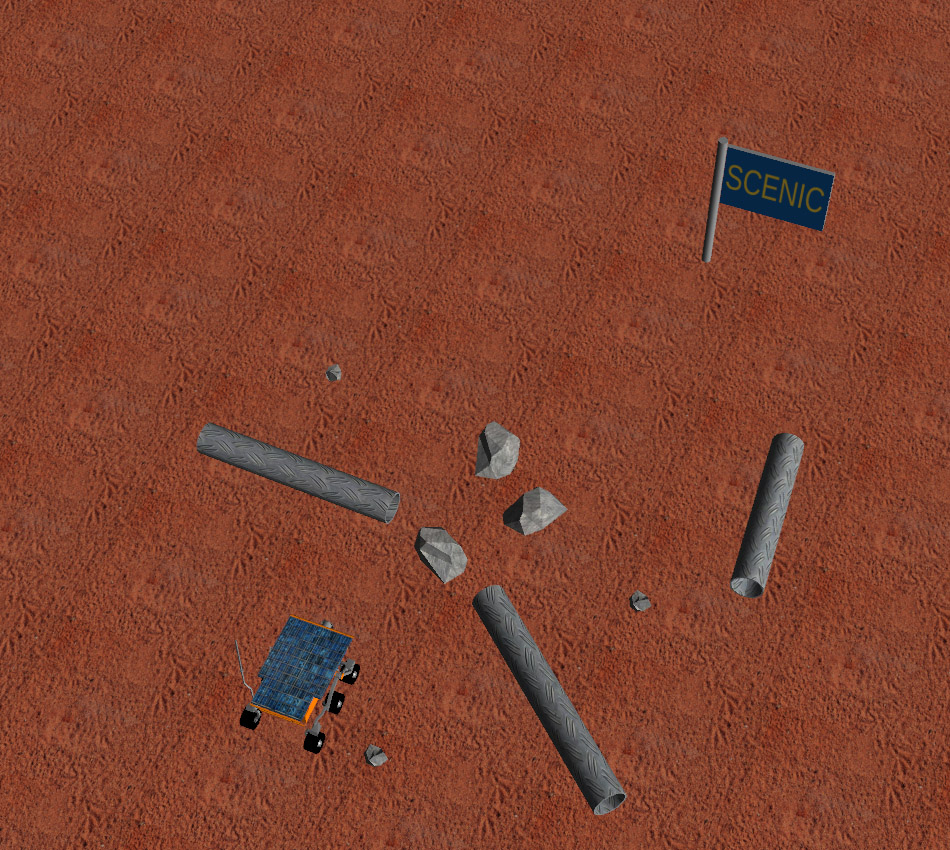

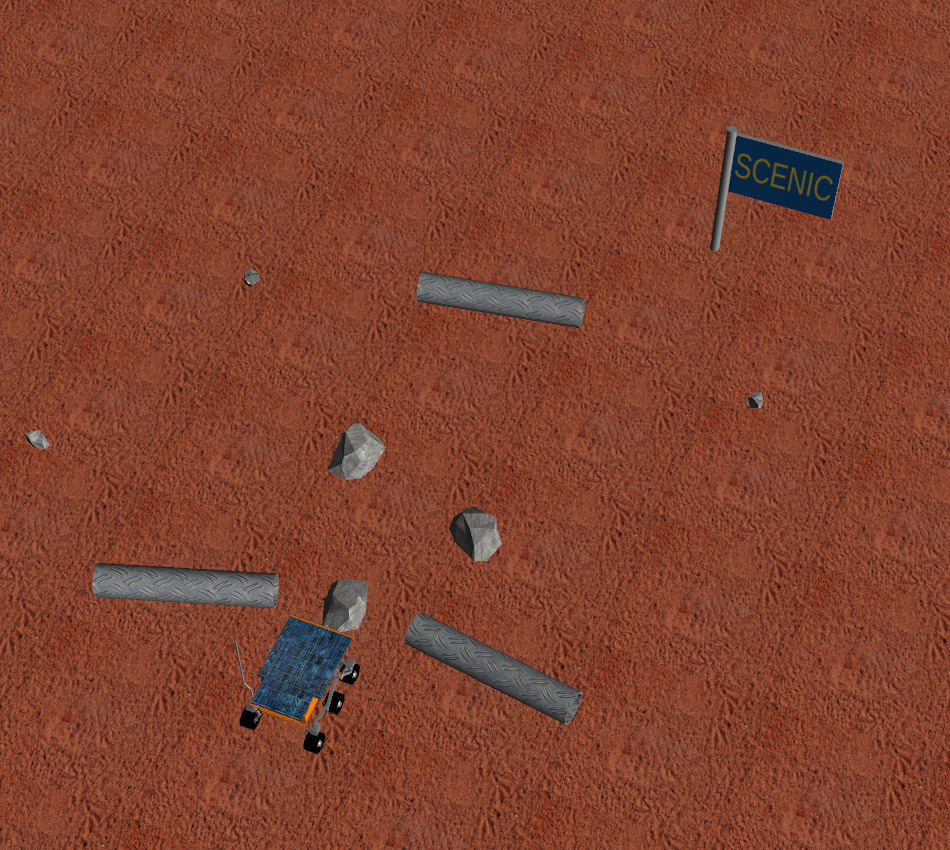

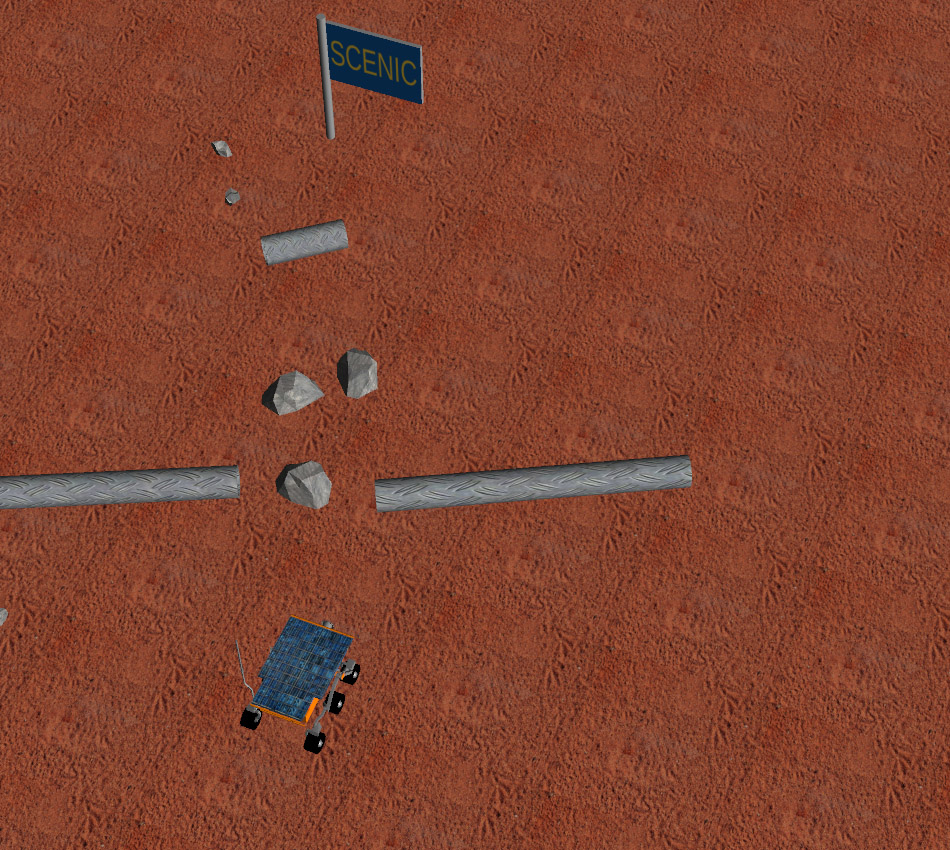

examples/webots/mars/narrowGoal.scenic. Several scenes generated from the

scenario and visualized in Webots are shown below.

A scene sampled from the Mars rover scenario, rendered in Webots.¶

Further Reading¶

This tutorial illustrated the syntax of Scenic through several simple examples. Much more

complex scenarios are possible, such as the platoon and bumper-to-bumper traffic GTA V

scenarios shown below. For many further examples using a variety of simulators, see the

examples folder, as well as the links in the Supported Simulators page.

For a comprehensive overview of Scenic’s syntax, including details on all specifiers, operators, distributions, statements, and built-in classes, see the Scenic Syntax Reference. Our Guide to Scenic Syntax summarizes all of these language constructs in convenient tables with links to the detailed documentation.

Footnotes

- 1

In fact,

egois a variable and can be reassigned, so we can setegoto one object, build a part of the scene around it, then reassignegoand build another part of the scene.- 2

On the other hand, Scenic may have to work hard to satisfy difficult constraints. Ultimately Scenic falls back on rejection sampling, which in the worst case will run forever if the constraints are inconsistent (although we impose a limit on the number of iterations: see

Scenario.generate).

References